|

The story of

Lancaster KB-976 is an

interesting one since it was

both the beginning and, sadly,

the end of the first real flying

aviation museum in Canada.

I was a

pilot in the RCAF over a 10 year

period, Regular and Reserve,

extending from 1954 – 1964.

During that time I witnessed,

and actually participated in the

departure of several famous

types from Canada’s inventory. I

was last to check out on the

P-51 Mustang with 403 City of

Calgary Squadron RCAF and last

to fly the Hawker Sea Fury. And

then, I was the last to pilot

the Avro Lancaster in RCAF

service, but that is getting

ahead of the story.

The museum

story started when I was 25 and

ended when I was 29.

As the

Mustangs were retired from the

RCAF I obtained a contract to

fly something like 70 surplus

aircraft to their new owners in

the States. Milt Harradence, an

ex-403 Squadron pilot would

accompany me. While visiting the

old RCAF Station Macleod, in

southern Alberta to inspect

Mustangs stored there, we saw a

large number of Lancasters being

prepared for the melting pot. I

decided to save one as a

memorial to the many who trained

under the British Commonwealth

Air Training Plan, during World

War Two. Nearly 140,000 students

graduated from this program.

F/O Lynn

Garrison, 1958 aged 20

After some

negotiation, I purchased

Lancaster FM-136 without

engines. Four Merlins for the

ferry flight to Calgary were

borrowed from the RCAF and

FM-136 was serviced by

volunteers from local 886

International Association of

Machinists, working with

Canadian Pacific Airlines

Repair. It would be mounted on a

pedestal at McCall Field,

Calgary’s international airport

during the spring of 1962. (In

1993 I would return to Calgary

to block its sale, by the City

of Calgary, to the

Confederate Air Force. As a

result of this, it remains on

display there.)

Lancaster

FM-136 in February, 1962

immediately after being painted

for memorial.

As a result of

the Mustang ferry project, James

DeFuria, the American purchaser,

gave Milt Harradence, and me, a

pair of Mustangs that were

registered as CF-LOR and CF-LOQ.

Milt flew his for a while until

he just had to have a

Dehavilland Vampire. I found one

for him and he sold the Mustang

which now flies as Checkertail

Clan, N-1451D.

At this

point I decided to collect

aircraft for a museum and

started the Alberta Aviation

Museum with a box of letterhead

and portable electric

typewriter. There were

hundreds and hundreds of War Two

aircraft scattered across the

prairies, sitting in farmyards

since being towed from local

airfields by purchasers

interested in gasoline in their

tanks and other small things.

The basic aircraft remained.

Farmers were

pleased to help, and made their

surplus equipment available to

me. A local trucking company

supplied a vehicle to haul the

display items to the Shell oil

pipe yard in north eastern

Calgary. Shell was kind enough

to let me store my aircraft

there and use their rail siding.

In no time I

had 2 Mustangs, Bollinbrokes

(3), a Lysander, Fleet Finch,

Tiger Moth, Fairey Battle (2),

Avro Ansons Mark 11 and V,

Stinson Reliant, Fairchild

Cornell, Airspeed Oxford, Cessna

Crane, North American B-25,

Nordyn Norseman, Harvard, Yale,

2 Hawker Hurricanes, all

accumulated locally plus a

Supermarine Spitfire AR-614 from

the United Kingdom, an F4U-7

Corsair 133693 from France, a

B-24 (HE-771) Liberator from

India, a Dehavilland Mosquito

(RS700 – CF-HMS) from Spartan

Air Services, a TBM Avenger,

Seafire, and a few aircraft

purchased from the Canadian

government. A T-33 Silver Star

serial 21001, the first acquired

by the RCAF with 210 hours on

the airframe: (My son Tony, a

lifetime later, would purchase

the last RCAF T-33 133648) a

CF-100, Sikorsky S-51, a Vought

Kingfisher, salvaged from a

British Columbia mountain top,

and - unfortunately – two

F-86 Canadair Sabers in Golden

Hawk colours. In all, I

would have 57 aircraft, plus a

lot of bits and pieces, plus

others promised.

My then wife,

Evelyn, did without most things

a young woman would expect from

life, in order to find the funds

needed to acquire another piece

of history. She should be

remembered for this.

In 1963 I

founded the Calgary

International Air Show as an

annual event to fund and

publicize the project. It was to

be held each July. As we

were working up to the 1964

show, and final exams at

university, I was offered a

Lancaster for $1,500.00. There

was a scramble for money, and

$1,500.00 was real money in ’64,

especially to someone in school

with a wife and family. I had

just purchased a new house for

$12,200.00 and, in 2013, it is

worth something close to

$400,000.00 on today’s market.

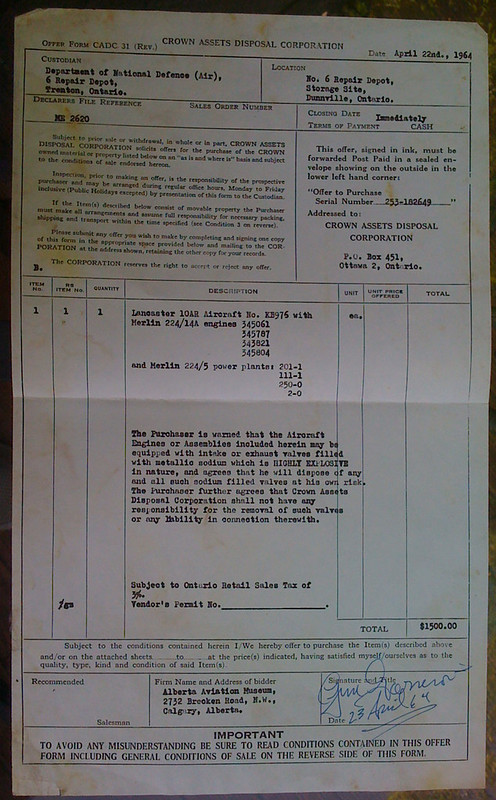

Original

bill of sale, courtesy of Lynn

Garrison

A few weeks

later Lancaster KB-976 was flown

into Calgary and parked in front

of 403 Squadron’s hangar. The

crew climbed out and left

everything but their headsets in

place, handing over the log

books before taking another

flight back to 408 Squadron.

The aircraft

arrived sometime in April, 1964

as we were planning that year’s

air show. As soon as I saw

KB-976 I decided I would fly it,

one last time, but didn’t tell

anyone. I would walk around the

aircraft. I would climb in the

starboard rear door, immediately

in front of the horizontal

stabilizer, and make my way up

to the cockpit, climbing over

the massive main spar, en route.

Without any Pilot Handling

Notes, I managed to start the

engines using experience from

the Mustang. Sitting there, I

would listen to the rumbling of

4 Merlins and watch reactions on

various system indicators.

I gradually

became confident in my plan.

Others

knew of my record, with other

types, but suggested the Lanc

was something else. I should

let an experienced Lancaster

captain fly the aircraft, with

me as copilot. At the time 403

Squadron had an ex-Lancaster

pilot with something like 1900

hours on type. Bill agreed to

show me the ropes and arrived

one Saturday morning for the

first lesson. We did a quick

external and then made our way

to the cockpit. Several

squadron mechanics stood by to

pull the chocks since Bill was

going to show me how to

taxi. He looked around,

as though expecting something.

Unsure of how to start the

engines, I got them going for

him. (Bill had always enjoyed

the support of a flight

engineer who handled things.)

After a few minutes my friend

waved the chocks away.

I stopped

this, pointing at the Brake Air

Pressure Accumulator gage which

was sitting near zero, while

those that indicated the

individual brake pressures sat

at a couple of hundred pounds.

Unlike

American aircraft, many British

types had air brakes with a

squeeze handle on the control

wheel. Pressure to left and

right brakes was controlled by

the rudder pedals with equal

pressure, to both, with the

pedals centralized.

A few more

minutes passed.

Impatient,

Bill again waved the chocks

away. I pointed to the

accumulator pressure, still near

zero, and he snorted something

to the effect that he knew what

he was doing.

Chocks away!

Bill opened

up the 4 Merlins, to overcome

inertia. The 4 spluttering

engines surged to a cutting

roar! The bomber moved forward,

accelerating. Bill reduced the

throttles, engines spluttering

to idle, and applied right

rudder, squeezing the brake

handle to swing us down the

taxiway.

With a

decreasing hissss, what little

pressure had built up was

rapidly depleted, having little

effect on the aircraft heading.

Throttles yanked back against

their stops, the Lancaster

rolled sedately forward to

become wedged in the poplar

trees surrounding the squadron

hangar.

Mixtures

into Idle-Cut-Off and props spun

into silence.

Bill climbed

out and departed. “He had an

appointment to take his wife

shopping.” I was left to hook a

chain around the tail wheel

strut and tow the Lanc back to

its starting point.

I was now

committed to a do-it-yourself

approach. I would captain the

aircraft. We needed a

Department of Transport approval

for one flight. The Mustang

ferry project had seen us have

the individual aircraft

serviced, and then signed out by

a qualified engineer. I would

use this procedure.

It was so

simple.

Wrong!

The

Lancaster type had once received

a full Certificate of

Airworthiness. In order to be

flown for a single flight, it

would have to go through the

entire process. By this time the

DOT knew what was on my mind and

threw this roadblock in my path,

sure that it could not be

overcome, without many thousands

of dollars in mechanical work.

We had

invited Paul Hellyer, Canada’s

Minister of National Defence, as

our Guest of Honor for the 1964

Calgary International Air Show.

He was a close friend of Art

Smith, a War Two Lancaster

pilot, DFC, and recent

Member of Parliament for

Calgary, South. Art was on my

air show committee. I asked Art,

and Art asked Paul Hellyer, and

the Minister said we could fly

it in RCAF colors, as an RCAF

aircraft for one last flight,

sending a letter to this effect.

I forwarded

the letter to our DOT office in

Edmonton with the question as to

qualification for the pilot.

Dick Beatty, the Regional

Director of Air Services phoned

me to say…”Multi-Engine

Commercial so you can fly it…”

He had known all along what my

plan was.

Brian B.

McKay had helped find the cash,

so he said he would go along.

Ralph Langemann decided he would

go, as did Joe McGolrick. Jimmy

Sutherland was proposed by Tony

McCarten, whose company had

serviced the Lanc for me,

since Jimmy had been a Lancaster

Flight engineer during World War

Two. People thought I was crazy

but the insanity must be found

in my crew, since they knew I

had never flown a Lancaster, and

had to carry me out to the

aircraft, due to my broken

ankle.

At the last

minute, someone had given me a

four page Xeroxed Lancaster

Check List so we buckled in

and followed the program,

searching for, and

discovering, new things, as we

went.

We were

ready to fire up!

We started

the starboard outer, then the

starboard inner, turning our

attention to the port side and

the other two, we lost the

starboard outer, and had

this pointed out by Brian

McKay. Got it restarted and we

were finally on the way with

McKay standing behind me,

holding a ten channel

Skycrafters transceiver on his

head, its headset over my

ears. We had assumed

that we could get the aircraft

radio to operate, but

couldn’t.

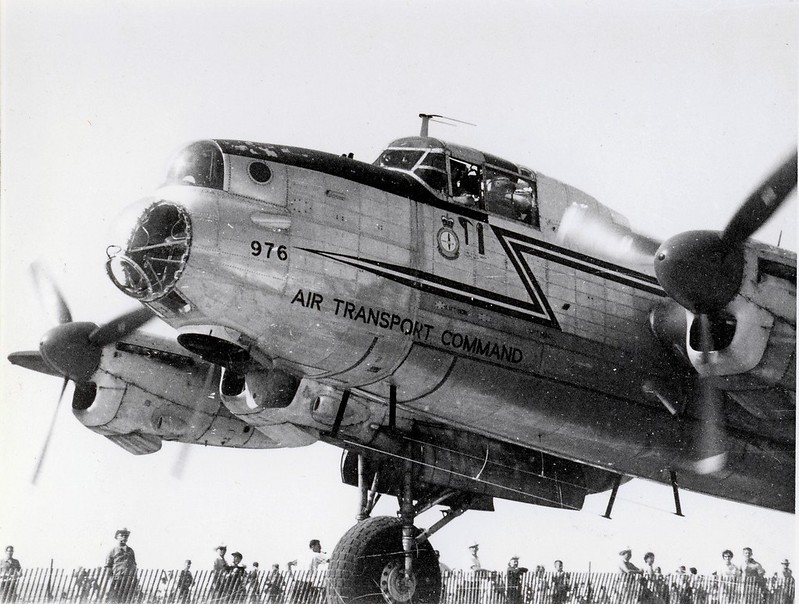

Photograph

courtesy of Ken Hyde

Photograph

courtesy of Ken Hyde

KB976

at start up. Garrison is just

visible in the cockpit window.

With my broken

ankle , I was relieved to have

a hand-operated brake system.

Cleared to

Runway 34, a short distance

from where we were parked, our

run-up was soon complete. I

moved onto the runway to

receive both a green light and

radio call clearing us for

take-off. The controllers

didn’t have much faith in the

tiny Skycrafters transceiver.

As part of

my research, I had talked with

Ben Budgeon who flew North

Stars, with the same engines.

He told me to lead with the

right throttles to overcome

torque, opposite to that of

the Mustangs.

Shoving

throttles forward, four

Merlins took over and launched

us down the runway, tail

rising as our airspeed built

towards lift off. Ralph

Langemann placed his hand over

mine, taking control of the

quadrant as we skipped into

the air. With a nonchalant nod

to Jimmy Sutherland I shouted

“Gear Up!” and he

reacted.

The take off, 4th July 1964

As the

undercarriage started to

cycle, there was a gigantic,

explosive bang. The cockpit

filled with dust and noise! We

were slewing to one side. I

thought we had lost an engine!

I don’t

know what the others thought.

Not a good

first flight!

An

explosion and engine failure

on lift of is not an

optimistic start.

The Lanc

straightened out.

The dust

cleared.

The four

Merlins were functioning.

What had

happened?

A lower hatch,

that previously housed the

radar antenna had blown up

into the nose compartment,

where Joe McGoldrick was

perched. The asymmetric

reaction was caused by the

main gear coming up, one at a

time.

No problem!

We were on

our way!

And so, Ralph

Langemann and I flew Lancaster

KB-976 around and across

McCall Field, at varying

heights and speeds,

accompanied by my Mustang and

a P-40 owned by Bob Warden.

During one pass we ran

directly over FM-136 on its

pedestal, creating a classic

shot of KB-976 and the

Lancaster Memorial.

Photo

courtesy of Lynn Garrison

Photo

courtesy of Lynn Garrison

FM-136 is now

a permanent display in

Calgary’s museum, without even

a mention of my name or

involvement. That’s life. At

least the aircraft was saved

for future generations.

We entered

the downwind leg, of our

approach, and Jimmy Sutherland

dropped the undercarriage. I

compensated with a touch of

throttle turning onto a 90

degree base leg and then onto

final, dropping flap as we

lined up on 34. “Gear Down”

and Jimmy Sutherland went into

action again. Some trim to

overcome control pressures on

the wheel.

Over the

fence. Throttle back. Hold

off, waiting for the big

bounce I had been warned

about.

Squeak…squeak… a greaser, and

we were rolling straight down

the runway, slowing at the

first turn off for the short

taxi back to our parking

place.

Braking to

a stop, crewmen placed metal

chocks in front of the Lanc’s

big main wheels.

Sutherland pulled four

mixtures into Idle Cut Off.

Our historic flight was over

as silver props spun into

silence.

Photograph

courtesy of Ken Hyde

Photograph

courtesy of Ken Hyde

The RCAF

Harvard demonstration team was

sitting there watching.

A Wing Commander in

charge, who was once commander

of the Lancaster Operational

Training Unit, murmured,

on seeing the landing…”Shows

what good training will do…”

One of his pilots said..

”Believe it or not, that was

their first flight.” The

Wing Commander wouldn’t accept

the fact until Art Smith

commented that evening, as I

was carried to the head table

and placed on a chair.

A week

later, when the swelling had

decreased, I had a DOT

medical, for renewal of

my Commercial License. Same

day I got a cast on my broken

ankle and would fly Harvards

on hail suppression for the

university holidays. Trying to

brake a Harvard, with a cast,

was exciting, but that’s

another story.

In April,

1964 the museum project took

on an official foundation. The

Air Museum of Canada was

incorporated as an Alberta

non-profit with 100 voting

shares. I held 98, my wife

held one and my mother held

the other. I named a few

friends to the non-voting

Board of Governors, a move I

would regret – in 1966 - when

these friends staged a palace

coup after Milt Harradence

attacked me.

Another

year passed and we were again

focused on the air show. This

time it would be in support of

The Air Museum of Canada and

would feature an RAF Vulcan

from 617 Squadron, plus a lot

of other aircraft. KB-976 was

a static display.

Photograph

provided by courtesy of Dick

Richardson

KB976

in RCAF colours just after

retirement as an airshow exhibit.

Over the past 12

months I had acquired a CF-100,

T-33, Sikorsky S-51 and now

scrambled to come up with cash

required to purchase a pair of

freshly overhauled Canadair F-86

Sabres in Golden Hawk colors.

I borrowed

$1500.00 and gave a Lien against

the Lancaster’s Title.

Milt

Harradence saw the Sabers and

had to have one. I explained

that we had acquired them under

a ‘mutilation agreement’

requiring cut main spars, if we

disposed of them. He just

couldn’t take this as an

adequate answer and continued to

press. After all, we had flown

together, he was my best friend

and had stood as my Best Man

when I was married.

Yet another

year passed, and the 1966 show

was sure to be a winner. The

Americans had promised 10

different acts, including the

USAF Thunderbird aerobatic team.

Milt was

still pressuring and asked if he

could have one, provided he got

government approval. I agreed

and said this must be in

writing. Charlie Drury, the

Minister of Commerce soon called

to say I could let Milt have a

Sabre. I asked for confirmation

in writing and – obviously – the

minister discovered what was

involved, and never wrote the

letter.

Milt

insisted that I sign the

aircraft over to him, in trade

for two Dehavilland Vampires.

I refused,

saying I had an agreement with

the government and had explained

this to him at the very start.

He offered to defend me in an

action that might result. Now,

Milt was one of the top trial

attorneys in Canada, and had

exceptional political

connections. I countered with a

comment to the effect that there

would probably be no action, but

the government would never sell

me another display.

The fat was

in the fire!

Milt sued

me! Calgary’s leading attorney

against a poor university

student, who happened, up to

that point, to be his best

friend! Unfortunately, Milt was

a person who would not be

thwarted, no matter what, by

friends, family – anyone!!

He also set

out to derail my application for

the annual air show by forming

The Calgary City Police Flying

Club with one member, a tame

sergeant. He tried to get

approval for his show, on our

dates.

He went to

the guy who had the Lien on the

Lancaster and bought the note.

He then demanded payment –

immediately!! Ernie Johnson

stepped in and took over the

Lien and the war went on.

I can

remember the last appearance at

the City of Calgary Aviation

Commission as Milt fought for

control. It was a frustrating

situation that saw me finally

react, with the comment: “You

must understand that the

displays are committed to the

Air Museum of Canada, and not

the City of Calgary…” This

drew a raucous chorus of

laughter, from the committee

members, and the meeting was

adjourned for another week.

I walked out

of the City Hall and stood on

its steps as my supporters.

All wished me the best of

luck, but they couldn’t go

forward to Red Deer. We shook

hands and I got in my car for

the drive to RCAF Station Namao,

outside Edmonton, Alberta, for

an agreement to stage my

American acts from their

facility. I then drove to Red

Deer for final talks with

aviation enthusiasts there,

having started talks two weeks

before. We agreed to transfer

the air show to Red Deer.

Calgary never had another air

show.

I had

something like 3 weeks to build

an organization to support the

project. Even as I was doing

this, Milt Harradence flew to

Nellis Air Force Base in an

attempt to have the THUNDERBIRDs

cancel their show. Team leader,

Lieutenant Colonel Ralph

Maglione refused and, when they

flew over Calgary, on their way

to Edmonton, they circled the

city with their smoke on as a

demonstration of support for me.

The 1966 team members have

remained friends, over the

years, and Mag retired as a

Major General.

The show was

a success.

The Canadian

government finally agree to let

Milt have the Sabre and this was

registered as CF-AMH

Photo

credit Harradence family.

About this

time I had some major offers

from the film business and

travelled to California for

projects, hoping to generate

funds for the first Canadian

flying museum.

I was soon

immersed in the Warbird

community, which wasn’t too

big in 1966. Milt and I had a

relationship with founders of

the Confederate Air Force –

Connie Edwards, Lefty

Gardiner, and Lloyd Nolan.

Milt was a Colonel but I never

joined. However, at my

suggestion, they started to

paint CAF in wartime colors,

replacing the overall white

scheme with red and blue trim.

I

sponsored the 1966 Los Angeles

International Air Show, at

Brackett Field, adjacent to

the LA County Fairgrounds with

over 50,000 attending the two

day production. Chuck

Lyford did an F8F Bearcat

routine that started with

short take-off and climbing

roll as wheels retracted.

Spectacular!

Over the

coming weeks, we all flew at a

number of shows, talking about

World War Two aircraft in our

spare time. The people from

Seattle were fascinated by my

tales of stored aircraft and

moved to obtain funds to

service and fly a few of my

items as first examples of a

flying museum. Since the

Lancaster, Vampire and

F-86 were already nearly

flyable it was decided to

start with these. Lyford and

Clarke had exceptional

contacts in the upper levels

of Seattle’s aviation, and

financial community. One of

Boeing’s hangars at Paine

Field was offered.

The

Lancaster could serve as a

cornerstone for what could

come. We would service it,

paint it and do the air show

circuit.

Chuck

Lyford, (P-51), Gil Macy,

(P-40) John Church, (F8F) Joe

Clarke, Jim Larsen, (one of

the great aviation

photographers, and

aeronautical engineers), and I

flew off to Calgary to on a

recce mission, to look at

KB-976 and see how many weeks

it would take to get the

Lancaster into shape. It had

been sitting there since July,

1964. We would then take it to

Paine Field, in Washington

State, where it would be

painted and readied for the

air show circuit.

Picture

by Jim Larsen.

May/June

1967 Calgary, McCall

Field. The

aircraft had been in

this spot since 1964.

Chuck Lyford in

the cockpit, John Church

standing under the

nose,and Gil Macy

standing under the rear

of the aircraft.

I had

tried to reach Ernie Johnson

by phone, prior to boarding

the flight, but he was

unavailable. This was a

normal condition with Ernie.

As one of Canada’s top

eye-ear-nose specialists, he

was always in great demand.

And so we

arrived in Calgary. I left

them at the terminal

building with instructions

not to go near Lancaster

KB-976 until I made

contact with Ernie to give

him his $1500.00 and clear

the Lien.

Since

my wife and family were

still living in our home,

I caught a ride to the

house to pick up my car

and call Ernie. He was

still not available.

Nothing unusual.

This was before the time

of cell phones, so I

headed back to the

terminal at McCall Field.

When I arrived, some

friends said my team had

gone across the field to

look at the Lancaster.

I

discovered them surrounded

by police. Someone thought

they were trying to steal

the Lancaster. When I

arrived, we were all taken

to the police

headquarters, in downtown

Calgary. Ernie Johnson

appeared and was

embarrassed at the

situation.

When we

arrived at the station, I

moved to make a phone call

to my wife, alerting her to

the situation, so she could

make a few calls to

strategic people.

At this

point, Detective Sergeant

Simmonds lunged across the

room, punching me in the

face with three quick blows,

yelling…”When you’re under

arrest you don’t make

calls!”

Another

policeman said…”He isn’t

under arrest!”

Simmonds

replied, “Well, he is now!”

About

this time, Milt Harradence

walked past the door and

looked it, spotting Clarke,

Lyford, Church, and Macy,

instantly recognizing them.

He grabbed an Inspector and

told him who they had and

they had better spring

everyone or there would be

some serious repercussions.

Joe Clarke’s father was

chairman of the American

Petroleum Association.

Lyford was married to Mary

Reed of the Simpson-Reed

Lumber group. Church’s

family headed a major pickle

corporation and Gil Macy’s

partner was Founder and

Chairman of the Flying Tiger

Line.

Everyone

else was released and, since

I had been arrested, I was

tossed in a cell overnight,

to wait for a Magistrate. I

can remember lying there,

passing in and out of

consciousness, not sure that

I would see the morning. No

one would call a doctor.

At 9

A.M. a Magistrate arrived

and the charges were

dismissed. My wife picked me

up and drove to the hospital

where I was admitted. Three

weeks later I was still in a

condition that precluded

flying. I had suffered some

broken bones and a

concussion.

During

those days, I had decided to

leave Calgary for good. I

visited Eric Harvey, the

founder of Calgary’s Glenbow

Foundation, one of the

world’s leading museum

groups. Harvey was the

richest man in Canada and

had been my father’s friend

since they served in World

War One. Harvey had been

with the Royal Flying Corps

and had already stated his

interest in supporting my

museum effort. He had

recently purchased the

Sikorsky S-51 helicopter for

me and was committed to

building a home for the

collection.

I

offered Harvey the

collection, free of

charge. He declined

with the comment. “The

aviation museum is a

personality based

organization. Without you,

it will fail.” At the

time I did not appreciate

the truth of this but

subsequent events proved him

right.

And so,

I left the collection stored

in Shell Oil’s pipe yard,

packed a U-Haul trailer with

some possessions, loaded my

family and set out for

California, to play a part

in the aviation and film

industry. I already owned

the collection of World War

One replicas accumulated, in

Ireland, for 20th

Century Fox’s The Blue Max.

I had my personal F4U-7

Corsair – THE BLUE MAX for

air show work, in the

States.

Lynn

Garrison’s Vought F4U-7

Corsair 133693

BLUE

MAX

Obtained

from French Navy, registered

N693M

Lynn

Garrison’s collection of

film aircraft Weston

Aerodrome

Ireland,

during filming 1969. Blue

Max Aviation, Ltd

My

Canadian associates found

there was more to the project

than being members of a

non-voting board of governors.

One by one they dropped away.

One

remained. Peter D. Norman took

over without checking the

documentation. Although the

Air Museum of Canada had been

incorporated in April, 1964,

none of the aircraft had been

transferred into the company

name. This small problem did

not stop this guy as he

disposed of my Supermarine

Spitfire AR-614, a Hawker

Hurricane, that was smuggled

out of Canada, by Rem Walker,

to become G-HURI, and a lot of

other items.

Even as

they tried to get KB-976 a

Certificate of Airworthiness,

under registration CF-AMD, so

it could be flown for

exhibition, (CF-AMC was on our

1909 Curtis Flyer), Ernie

Johnson’s interest in the

aviation museum faltered when

someone offered him $150,000

for Lancaster KB-976 and that

was really the final straw in

breaking down any possibility

of Calgary having a meaningful

aviation display. Since he had

a Lien for $1500.00 against it

he felt he also had the right

to sell the aircraft, and he

did. So much for team

cohesion, and all that

emotional garbage.

I never

sold a single item, although I

did give pieces away, to help

others. One set of Hurricane

wings made the Hurricane

project, by Neil Rose in

Vancouver, Washington, a

success. And I donated

my Vought OS2U Kingfisher to

the North Carolina Battleship

Commission. It now has a

place of honour on the

USS North Carolina.

Eight or nine

of my original collection

remain in Calgary.

My

Mosquito, and one of my

Hurricanes are now being

rebuilt at the Bomber Command

Museum in Nanton, Alberta. The

City of Calgary had tried to

sell them to someone in the UK

for several million, but were

stopped by a new generation of

enthusiasts. Supermarine

Spitfire VB AR-614 is now a

beautiful display at Paul

Allen’s Seattle-based aviation

museum. My Vought

Kingfisher is now displayed on

the North Carolina Battleship

Commission, having been

rebuilt by friends at LTV

Aerospace in Grand Prairie,

Texas.

My son

Patrick and I still have three

aircraft from the film

collection, a Fokker Triplane

and 2 SE5s. Well, actually,

the 2 SE5s are his alone.

I didn’t

return to Canada until the

June 1986 death of Rod, Milt

Harradence’s son, in a plane

crash. I had baby-sat him as a

young child and returned after

the funeral, with my sons Tony

and Patrick, to see Milt and

his family. It was sad that we

had lost all of those years.

I moved on

to other things and presently

head the Haitian Children’s

Fund, a team that has created

the Satellite School System.

It has a studio and uplink

system that will bounce

classes off an Intelsat

satellite to any point in the

country. The lessons will be

collected with a dish antenna,

receiver and wide screen TV,

powered by solar panels, an

inverter and batteries.

We might

raise the literacy rate by a

few points in the first 12

months.

Most of

the others have passed on,

leaving Ralph Langemann and me

as the last men standing,

after a wild and lengthy

barroom fight.

Perhaps

they did me, and the Haitian

kids, a favor by destroying my

hopes of creating and heading

a flying aviation museum.

Of course,

Lancaster KB-976 flew across

the Atlantic to join the

museum world there, finally

bouncing back to Kermit

Weeks’ museum in Orlando,

Florida, but those are other

elements of KB-976’s ongoing

saga.

Lynn Garrison, July 2013

|